No products in the cart.

5 art trends to watch for in 2023 — but only with young black artists’ references

As we settle into the new year, it is time to look at the latest trends in the art produced and exhibited in 2022 to risk predicting what will change or continue in 2023. Based on the analysis of some of the biggest international art events, fairs and magazines, Artkofa selects five possible creative directions – technical or thematic – to keep an eye on throughout this year. For each trend, we have chosen as references works one of our favourite young, African or Afro-diasporic, artists.

In between figuration and abstraction

Through Ruth Ige

It is well known that figuration has recently found its way to the top of auctions, galleries and museums. While there still is, of course, plenty of room for novelty, the art market seemed saturated with it by the end of 2021. If, on the one hand, some attribute the emphasis on the body and the pictorial as a counter-movement to the physical rejection experienced during the pandemic confinement, on the other, in the particular case of black figurativeness, it might be an attempt to regain agency over the white anthropocentric image that prevails in art spaces and in Western imagery for so many centuries.

The trend continued into 2022, with high profile figurative exhibitions taking over prestigious institutions such as Tate Modern, with a large-scale show dedicated to Lubaina Himid; Palays de Tokyo, with the French debut of Brazilian Maxwell Alexandre’s remarkable “New Power”: and Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, that staged Spain’s first ever retrospective for Alex Katz. In the coming years, however, these currents may change their flows. Hanna O’Leary, in research compiled by ÌMỌ̀ DÁRA, reminds us that, historically, the art produced on the African continent had been much more marked by abstractionism. According to the Head of Modern and Contemporary African Art for Sotheby’s London, the international market demand for the black body should break down — and she predicts: “in the long-term, abstraction will,” again, “come more and more to the fore.”

Until then, something in between is slinking in. In Ruth Ige’s work, for example, the boundaries between the abstract and the figurative blur as in a wet kiss or a misty sky. In many of her works, it is still possible to distinguish human outlines — but a distanced glance is enough to discover other forms, geometric shapes, ghostly figures. Drenched in intense, icy, neon and quite authorial shades of blue (after Klein Blue, could we risk coining an Ige Blue?), partly inspired by the indigo fabric adire by the Yoruba people, her most recent quasi-portraits offer nothing but an enigmatic, unexpected and complex depiction of blackness. In Ruth Ige’s worlds — abstraction allows the transfiguration of a universe of its own, with new and variable ideas of beauty, ugliness and order —, there is something hypnotic that leads us into a deep dive, seduced as if by divine entities that can never reveal their faces.

Installation view of Ruth Ige’s artwork, “Between Two Dimensions”, at Roberts Projects LA, 2022.

Sewing temporalities with textile art

Through Manlanbien Marie-Claire Messouma

It is unarguable that the last edition of the Venice Biennale was swathed in weaving and stitching. Textile artworks were, without doubt, the great protagonists of the most anticipated and important contemporary art event in the world. In the Polish pavilion, occupied for the first time by a Roma artist, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas told the stories of her people through 12 astonishing textile installations, composed of collages of torn garments belonging to the subjects of her works and other discarded materials. Through the work of Swedish Britta Marakatt-Labba, embroidery was also a storyteller of her ancestors, the Sàmi indigenous community. In the Giardini’s Central Pavilion, we discovered knitted paintings of Rosemarie Trockel and the soft, fibrous sculptures of Mrinalini Mukherjee. In the Arsenale, we found Chilean Violeta Parra’s political arpilleras, Haitian Myrlande Constant’s vibrant and heavily laden Vodou-themed handmade flags and pioneer Safia Farhat’s massive carpet pieces.

The list could go on, but what matters is to realise that, after being long neglected by a colonialist and sexist art history, textile art has been claiming more and more space and attention in galleries, fairs and art biennales over the years. The sewing process unfolds, mends, makes and remakes relationships that could be physically and temporarily close or far, in a gesture of constant and unstoppable search. Thus, textile art invokes a linkage with ancient forms of remembrance, besides materialising the time, risk and movement of touch in a medium that has something sincere and comforting.

For millennia, in Africa, the making and exchange of countless types of fabric have been crucial factors in connecting parts of the continent with each other and the rest of the globe. A reference of engaged and sublime textile work, which vibrates the continuity – and discontinuity – of these ties in each thread, Manlanbien Marie-Claire Messouma draws inspiration from the traditional practices of the matriarchal Akan society, in the Ivory Coast, to map and create narratives between living testimony and the past traces of (still possible) histories, civilizations and ways of living. Intertwining memory and black feminism (in not at all obvious ways), the artist activates her textile pieces with a performative component, inviting the viewer to situate and ritualise themselves within or before this poetic space.

“#3#Map” (2019), by Manlanbien Marie-Claire Messouma.

Dreaming with another (sur)reality

Through Gideon Appah

Do surreal times call for surreal art? Is it possible that we live in too much absurdity and with too little imagination?

To think about these questions, we turn, once again, to the last edition of the Venice Biennale, this thermometer of art and time: “The Milk of Dreams”, title borrowed from the book of same name by Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011), presented as curatorial motto an investigation on the capacity for bodies and for the category of the human itself to metamorphose. Also in 2022, and in the same city, the exhibition “Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity” coloured the walls of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection with artists such as Kay Sage, Maya Deren, Dorothea Tanning, and Leonora Carrington herself; in London, an extended, multicontinental surrealist retrospective occupied the Tate Modern from February to August, “Surrealism Beyond Borders”; across the Atlantic, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an exhibition dedicated to the visionary Meret Oppenheim brings together almost 200 of her original and challenging pieces, on show until March this year.

In synthesis, the appeal of surrealism seems to be twofold. Entering the post-truth era, when it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish real images from those manipulated, it is as if surrealism could rescue the possibility of satirical criticism – which, to be effective in times of barbarity made banal, of the ridiculous made reasonable, must become twice as barbaric and twice as ridiculous. Secondly, as the world appears as an ever more global catastrophic curse – although it is important to remember that the “end of the world” that is now seen on everyone’s horizon arrived much earlier for many original communities and peoples –, surrealism may offer an alternative space of existence. A displacement, utopian or dystopian, to other planes of reality, to other past, present or future times in which life can still inhabit and flourish.

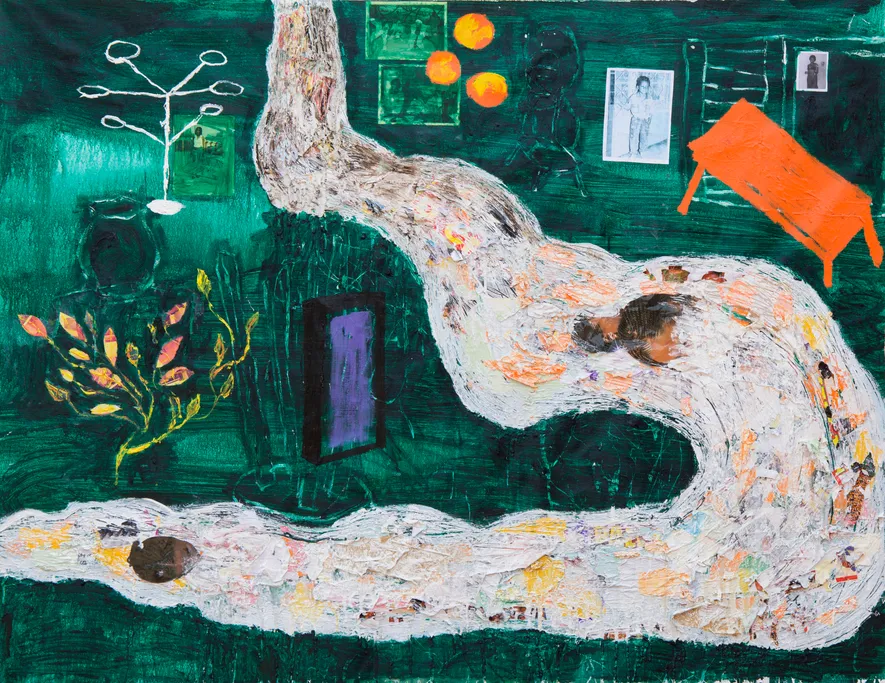

Such is the world depicted by Gideon Appah, Accra-based Ghanaian artist who navigates – sometimes quite literally, as water and river are constant motifs in his paintings – between his own family memory and his country’s history. Owner of a collection of national newspapers from the 1960s, Appah mixes and dyes archival materials, personal photographs and thick, rough layers of acrylic to (re-)create the ethereal, misty space of memories and mythologies, whether shared in the intimacy of his domestic environment or the collectivity of the city’s public life. The factual and concrete stories which, however, the artist can only experience as a tale or mirage, gain, here, a character that is both nostalgic and prophetic: where does the past go? Is it possible to grasp it? How can it become present and future?

“Nsuteen buom (River With a Room)”, from “Pokuo’s Place” (2017), by Gideon Appah.

Ecofeminism’s alternative, hybrid, wonderful worlds

Through Josèfa Ntjam

“Woman” was Dictionary.com’s word of the year in 2022; “Permacrisis” was Collins’.

Ecofeminism is not exactly a recent movement. The term is said to have been used for the first time in 1974, in the book “Le Féminisme ou la Mort” – which also introduces the expression “phallocrate” –, a work by Françoise d’Eaubonne, a French activist who firmly supported the liberation of Algeria during the decolonisation war. Founder of the “Ecologie-Féminisme” association in 1978, she is one of the first to identify the oppression of women with the oppression of nature. The recognition of the various systems of oppression that reinforce each other, feeding off the many binarisms that govern hierarchies and segregation in the world, is the core of a politically-engaged thought that has become popular with, for example, Vandana Shiva, Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, and, in the arts, with Helène Aylon, Agnes Denes, Ana Mendieta, Aviva Rahmani, Cecilia Vicuña and many others.

In recent years, the term “Anthropocene” has gained ground among academics, curators and artists, who reflect on the particularities of this new geological period from its impact on the redefinition of politics, economy, ecology and art. Thus, in a world already deeply wounded and exhausted, ecofeminism lays bare the mechanisms of power and performance that tell us about human history, while inviting us to recover our response-ability and agency as creative subjects: “Feminism is the joyful affirmation of powerful alternatives,” says Rosi Braidotti. In general, ecofeminist art cuts across different media, gathering strength in the blurring of boundaries – between artistic disciplines, between humans and non-humans, nature and culture, biology and technology. One no longer longs for purity, there is nothing left that is untouchable and that can be written with a capital letter: all great ideals fall apart. There is no time and space left for History, what really counts is the interconnectivity of a mesh of stories yet to be told.

Raised as a child of the Internet and the African diaspora, Josèfa Ntjam reaches out for many diverse sources of inspiration: science, astrophysics, biology, mythologies, afrofuturism, magic realism, speculative feminism, technology, music, performance and poetry. In an interview with Contemporary And, the artist explains that her interest in ecology and the organic world reflects a concern to think of “their [plants, animals, organic materials and substances] evolution and techniques of survival and multiplication” as processes related to “certain modes of resistance and action that have been used by minority and oppressed groups of people across history”. From this melting pot of contaminations and hybridisms at all molecular-social levels, new worlds, with no heroes nor fixed identities, are born and transformed.

Installation view of Josèfa Ntjam’s artwork in group exhibition “Anticorps” at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2020.

Conceptual sculpture at its best

Through Kayode Ojo

Veronica Ryan, acclaimed for her sculptural assemblages that evoke themes of belonging and displacement through the landscapes and memories of her childhood, had her first solo show at Alison Jacques last year, as well as winning the great Turner Prize. First Black woman ever to represent the United States at Venice Biennale, Simone Leigh’s monumental success – having been recognised with the Golden Lion award for the best participant in the central exhibition – also stands out: guided by references such as early Egyptian terracotta pottery and 19th-century African American face jugs, the artist creates large, mysterious sculptures in homage to the black and female body, playing with the absences, iconographies and cultural appropriations that traverse the West.

The last annual art review carried out by the editors of frieze confirms: if 2021 was the year of painting, 2022 was the year of sculpture. From the analysis of the works exhibited at the Venice Biennale and at the New Museum Triennial, one can see the progress and the emphasis on sculpture, particularly conceptual sculpture, as a privileged medium for artists and art institutions – perhaps due to the rediscovery of the significance of materiality in an increasingly virtualized reality, or perhaps due to the recognition that this new materiality, no longer the same as it was a few decades ago, may be even more subject to experimentation in contemporary times.

On the radar of Forbes and Harper’s Bazaar’s Under 30s artists, with an unique and seductive sculptural work – complemented by a beautiful, intimate body of photographs with a touch of Nan Goldin –, is Kayode Ojo. In the last five years, the American-Nigerian artist has emerged as part of a new generation of creatives with a language already very much his own and mature. Interested in male psychology and sexuality, Ojo’s pieces seem to reach the minimal unit of our circuits of pleasure and displeasure, materialising the fetishes, performances and gestures that participate in them. As in his photographic records, often overexposed or showing obliterated subjects, these are strange compositions, which offer themselves to the public’s gaze in a paradoxical way: inviting and expelling us, bringing us closer only to push us further away. With attentiveness, we might be able to decipher his sculptures also as framings, images, as critical spectacles: in the end, each object is exposing and playing with our own expectations – and desires.

“Walk Two Moons (Berlin | Tiffany & Co.)” (2022) by Kayode Ojo. Photography by Diana Pfammatter. © The artist and Sweetwater, Berlin.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.